The brutal civil war that ravaged Sierra Leone for over a decade left hundreds of innocent citizens with life-changing injuries. While aid initiatives involving 3D printed functional prosthetics already exist, they rely on designing and shipping from afar, limiting their effectiveness by adding extra time and costs to the process. Surgical resident Lars Brouwers, of Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, and PhD-candidate of the Elisabeth-Tweesteden hospital, the Netherlands, believed that there must be a better way to get aid to those affected.

Providing faster, cost-effective aid

Having previously worked with 3D printed anatomical models at his PhD position at the Elisabeth-Tweesteden hospital, Lars Brouwers had the vision to help create “very cheap prosthetics that everybody can afford, and quickly.” He came to the conclusion that the best solution was to bring the technology to Sierra Leone, to provide knowledge and materials to local citizens in need.

We could not just bring the 3D printer and leave it there, we wanted to start a sustainable project.

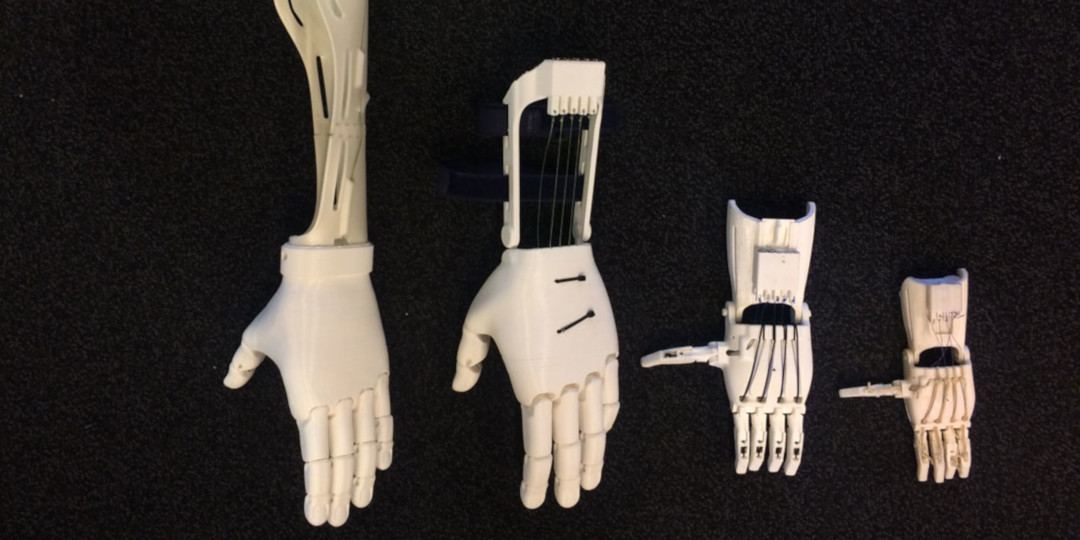

With a clear objective in place, Brouwers prepared for his journey by developing effective, natural-looking prosthetic designs which could be 3D printed easily. Equipped with an Ultimaker 2+, and enough material to last a whole year, he and colleague Dr. Wouter Nolet, a tropical doctor in training, began a three-week road trip, starting in the Netherlands, passing through Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Guinea, and ending at the Lion’s Heart medical Centre in Sierra Leone, to provide knowledge and skills to affected locals.

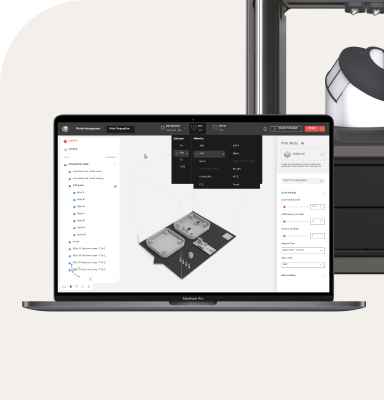

Lars Brouwers had worked with 3D printing during his PhD position at the Elisabeth-Tweesteden hospital in the Netherlands

Arrival in Sierra Leone

When Brouwers and Nolet arrived at the Lion’s Heart medical Centre, local prosthetic engineers turned out to see the equipment, and the response to the new 3D printing technology was very positive. Locals were excited to be trained on its use, as up to this point they had been creating prosthetics by hand.

3D printing prosthetics produces accurate, consistent results in a less labor-intensive way

The unrest in Sierra Leone had left the whole country with a damaged infrastructure, where power failures are frequent. The Ultimaker 2+ needed to be installed in a location with constant access to electricity to work. The clinic had been fitted with a special uninterrupted solar power supply to prepare for any power outages, which is where the printer was temporarily placed.

The local prosthetics specialists’ passion and dedication made it no problem to drive over sixty kilometers on small motorbikes to the clinic every day. However, after some time, it became clear that a more accessible location would be needed. Brouwers and Nolet are currently working to overcome this challenge by creating a mobile solar-powered system that would provide power for the printer in a more central location.

More than just prosthesis

The Ultimaker 2+ found uses alongside creating affordable prosthetics. Important tools, such as umbilical clamps, which previously needed to be delivered by boat as part of a long and expensive process, were able to be printed on-location and on-demand, in often time-sensitive situations. Furthermore, Brouwers and Nolet discovered that printing anatomical models for teaching purposes were of added value as well. They printed a thoracic spine in order to teach medical officers how to perform spinal anesthesia. Brouwers reports that they are seeking more opportunities to provide anatomical models.

Closing the global gap

With the seed of innovation planted, and all the necessary tools and training in place for locals to continue rebuilding, Brouwers returned to the Netherlands. The trip was “a real adventure, very special”, reflects Brouwers. “The opportunity of seeing the true nature of the African continent” and “...meeting such nice people everywhere we went” were some of the highlights of the trip.

Nolet remained in Sierra Leone as part of his medical training. He, the local team, Brouwers, and the 3D lab of the Radboud University Medical Centre are able to keep in contact through email and Whatsapp, to help with the handover and adoption of the technology. Local specialists can send pictures of any necessary parts they need, where Brouwers and the 3D lab can digitally design and transmit designs back to Sierra Leone, where they are printed on site. However, the main goal of this project is to empower the locals and give them self-sufficiency, avoiding constant remote support. Brouwers and Nolet expect the process to take a few years.

This project will eventually be in their hands. It has to become fully local in order to reach its objectives. We will be there for as long as they need us, it doesn’t matter how long it takes.

Brouwers and Nolet have been nominated for the Albert Schweitzer award 2018. For more information, you can find Lars Brouwers on Twitter.